In my short story, “Memento Mori,” private investigator Adam Cole becomes involved in the hunt for a murderer whose signature is taking photos of his victims before and after death and sending them to their aggrieved families. While I am not aware of any Victorian English murderers who used this method (Harvey Glatman, the “Lonely Hearts Killer” of 1950’s Los Angeles, did something similar), there is a kernel of truth to the post-mortem photography used in the story.

The term memento mori is itself a Latin phrase for “remember, you will die,” or “remember, death.” This was meant to be a bit of Stoic philosophy, reminding the living that death was inevitable, waiting around the corner for us all, so it was best to make the most out of life while one still had it and to proceed cautiously with any decisions affecting it.

The Victorians took the philosophy a step further and in a slightly altered and ghoulish (yet also sweet) manner. To them, the idea of the memento mori was to capture an image of a loved one. Given the rare and rather involved and expensive processes that photography required from its inception in the early Victorian Era until later in the 19th Century, taking and keeping plenty of photos of loved ones throughout life was just not practical, especially for the middle-class and poor. So, when a loved one passed away unexpectedly, a photographer was often hired to photograph the family with the deceased so they could have at least one cherished permanent record of their lost loved one before burial.

Before this, the only means of holding on to a lost loved one was through memories, personal trinkets and clothing, locks of hair, and, if it could be afforded, portraits completed by skilled artists. By the middle of the century, as photographic techniques improved (while remaining complex and expensive), the notion of the memento mori photograph took flight.

Often, the deceased would be dressed up and propped up to look as though they were sitting and, sometimes, would have their closed eyelids painted over to look as though they were open and staring lively. This was all to showcase simulated life in the deceased. What is interesting, given the long exposure times required to take a photograph, family portraits will often show the living members as slightly soft and blurred due to movement – the dead, on the other hand, are crisp and focused. In other photographs, the deceased may clearly be displayed as such, with eyes closed, perhaps slightly slumped over, or even laying in state in a bed or casket. One could argue that they just appeared to be asleep in these poses.

Most of the photographed deceased were infants and children. The mortality rate due to disease remained high in children under five until later in the century when sanitation and medical treatment improved. And as can be expected, grieving parents then as now needed some image of their child to hold on to, and the memento mori photograph was the best and most sophisticated last-ditch means to do so. The tradition continued into the inter-war years, and while some cultures may utilise some form of it to this day, most western cultures have long-since ceased to depend on it.

In the latter decades of the Victorian Era, the police would also use post-mortem photography, but not as a treasured keepsake. If a body was found and not immediately identified, it would be photographed so that the image could be used for later identification. Given the rather uncommon and primitive means for refrigeration at the time, in-person identification of the body at a morgue or hospital had a severe time limit, so preserving the deceased’s image could allow future documentation to occur whether it took days, weeks, months, or years.

This process would eventually evolve in another way. It struck the police that, beyond just photographing a corpse in the morgue for identification, they would do well to photograph a murder victim in situ, so that an image of the original scene could be kept for evidentiary purposes. From this, modern crime scene photography was born. Before, such scenes relied on the memories and notes of the original investigating officers, and in some rare instances sketches that were produced. It seems strange that the idea of photographing a crucial scene such as a murder did not occur – or, at least, was not taken seriously – until about 50 years after the first early cameras were developed. The first reliably known incident of this now-invaluable technique occurred on Friday, November 9, 1888, when the London Metropolitan Police took at least two in situ photographs of Mary Kelly, a young woman who had been brutally murdered and mutilated in her own bed. While her name may be known, that of her murderer eludes investigators to this day – he is known only by the sobriquet Jack the Ripper.

Some of the references provided below display numerous examples of memento mori photographs from the Victorian period. Many more can be found through simple Google Image searches. Peruse at your own peril.

References:

Article: “Taken from Life: The Unsettling Art of Death Photography.” BBC. June 2016.

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-36389581

Wikipedia entry: Post-mortem photography.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-mortem_photography

Article: “Memento Mori – Remember That You Have to Die.” George, Philip. The Conversation. June 2015.

https://theconversation.com/memento-mori-remember-that-you-have-to-die-42823

And please check out my mystery short story Memento Mori, available free to read below:

"Memento Mori"

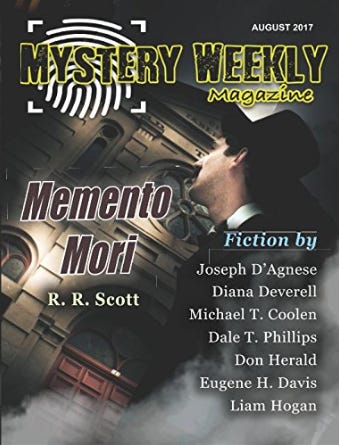

Welcome to the Case-Book of Adam Cole! Below is the first Adam Cole short story, Memento Mori. It was originally published in the August 2017 issue of Mystery Weekly Magazine. Copies of the complete issue are still available through the MWM website and through Amazon.